The Making of a Scholar

It was an inauspicious beginning for someone who contributed to our understanding of the role of diet in human evolution.

“I was terrible in school,” says Peter Ungar, Distinguished Professor of anthropology and director of the University of Arkansas’ Environmental Dynamics Program. “My mother saved all the old report cards, and they were like, ‘if Peter applied himself, he could do very well.’ I just got mediocre grades. Even in high school, I pulled it out, in the 11th hour, to get myself into a decent state school. I think I was 79th out of 656 in my class. That's okay, but it's not… I was never outstanding, never in any of the above-level classes or anything like that.”

This did not mean Ungar wasn’t curious about the natural world. In fact, a foundation for science had been laid early in childhood. In the second grade, while attending public school in Queens, Ungar’s class took a field trip to the American Museum of Natural History in Manhattan. He saw the dinosaurs and big blue whale.

“I decided I wanted to be an archaeologist,” he says. “Of course, I had no idea what archaeology was at the time. It’s not whales and dinosaurs, but what did I know?”

About five years later, Ungar’s father, a theoretical astrophysicist and mission scientist for NASA, took young Peter to see Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. The movie blew his mind. Today, in his office on the third floor of Old Main, Ungar has a framed still image from that “crazy movie.” He keeps it on his desk, so he can look at it when he’s writing about the diet of primates and early humans. The picture depicts a critical moment in evolution, the moment when the human ancestor picks up a bone from a pig and realizes that with tools and a brain, he need never be hungry again.

“That was a fundamental shift from animal to human,” Ungar said, “that I found really fascinating.”

SINKING HIS TEETH INTO RESEARCH

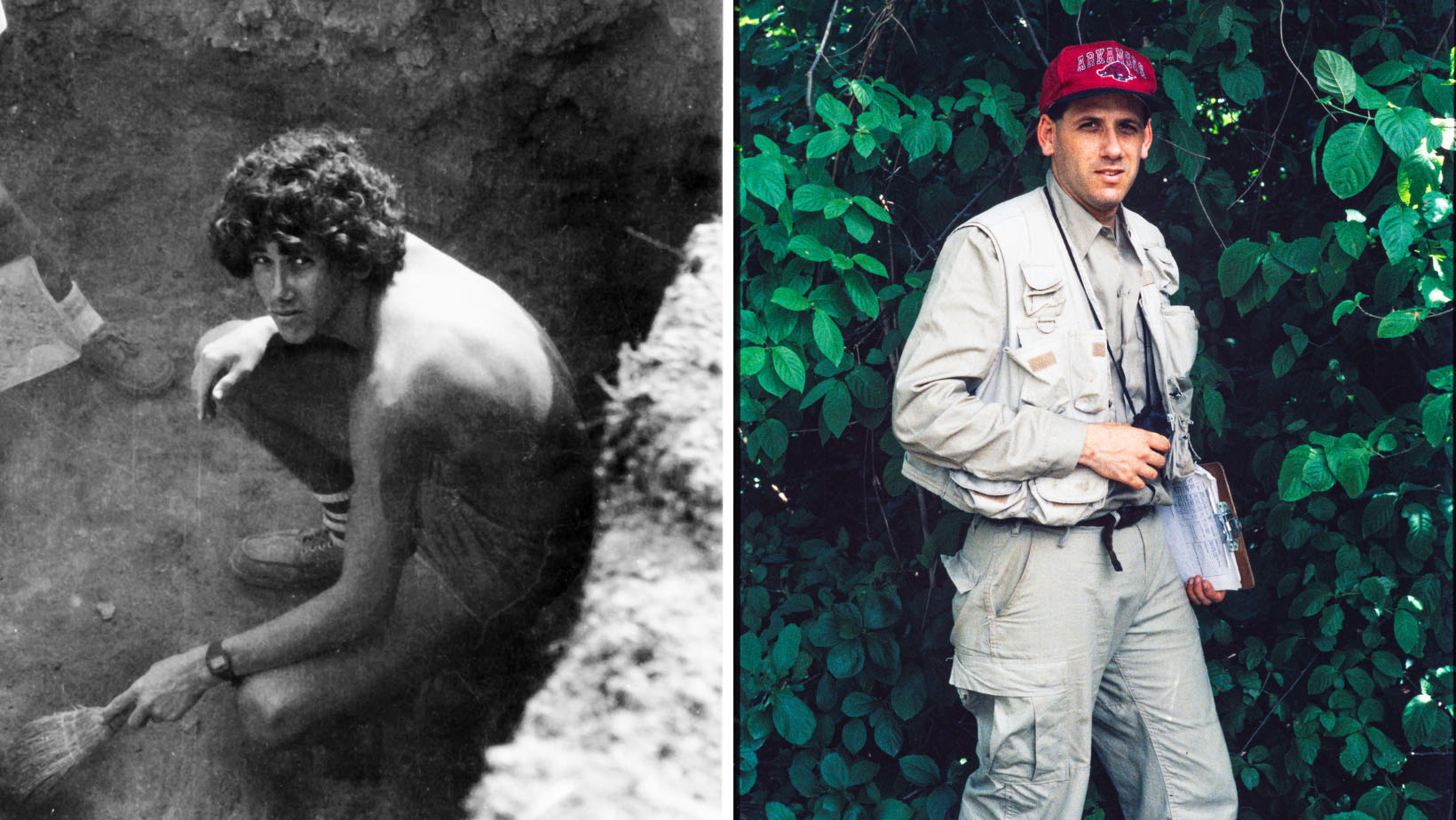

As an undergraduate at Binghamton University, a New York state university, Ungar followed his expanding interest in archaeology and early humans. He was influenced by two “wonderful” mentors, Margaret Conkey and Philip Rightmire. At Binghamton, Ungar started making As, and as graduation approached, he knew he wanted to keep going.

He was accepted into the doctoral program in paleoarchaeology at the University of Wisconsin – at the time, one of the best in the U.S. But two things happened there that changed his course again. The first thing was dumb luck; the researcher he was hoping to work with was on sabbatical. Secondly, the academic discipline of archaeology at the time was going through “a sort of midlife crisis,” and scholars were intensely focused on theory, something that held little interest for Ungar. “I didn't want to sit around talking about what we can and cannot know,” he says. “I wanted to know something.”

This led Ungar back to New York, to Stony Brook, a public university on Long Island. Two scholars there, John Fleagle and Fred Grine, were among a group of anatomists and biological anthropologists who were working through important details about primate and human evolution.

While he was initially interested in the first hands that had made stone tools, things changed when Ungar took Grine’s course in human evolution. One day, when Grine was assigning projects and Ungar was without one, the professor asked the student if he wanted to study teeth. Grine’s lab was looking at microscopic tooth wear of incisors, and he asked Ungar if he had any interest in measuring scratches in the pits on these teeth.

“I said, ‘Sure, why not?’”

Maybe it wasn’t as huge as Arthur C. Clarke’s early man-apes differentiating from other animals, but nevertheless, for one scholar still trying to find his niche, this was a pivotal moment. In that initial project, Ungar found some “interesting results” – differences between two fossil species with regard to scratches on incisor teeth, and “it just sort of blossomed from there.”

One way it blossomed was the discovery of a novel approach to understanding, or perhaps reconstructing, the past. While focusing on tooth wear, Ungar was also taking classes with Fleagle, who pioneered the idea of using living primates as models to understand the past. Until this time – the mid 1980s – most researchers focused on comparing fossils to fossils. For Ungar, Fleagle’s new approach was seminal.

“If you understand the anatomy of living animals and their behavior,” said Ungar, “then maybe you can infer behavior from anatomy and fossils.”

That behavior, of course, is related to diet, how and what early humans ate, which in turn explains a lot about how humans evolved.

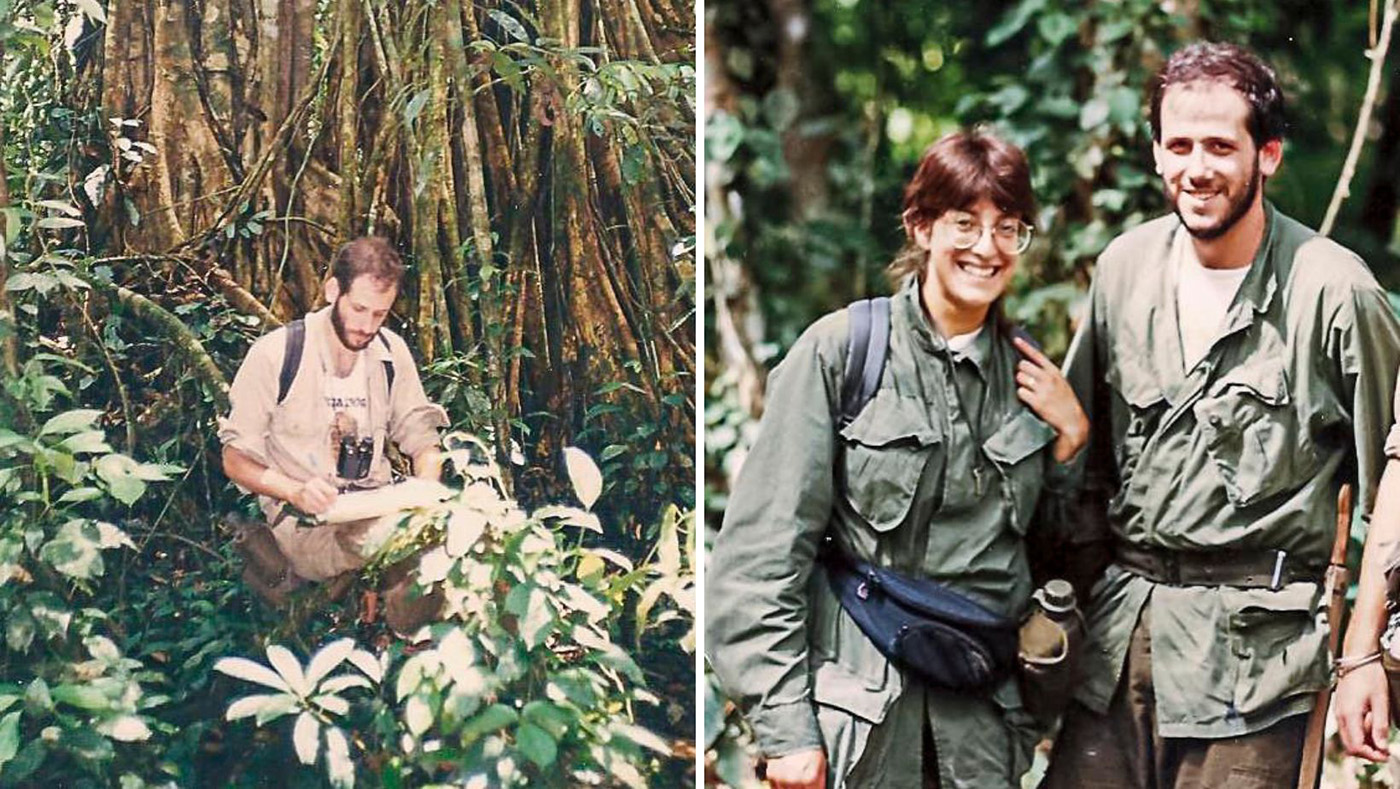

REVELATIONS IN SUMATRA

For his doctorate, Ungar took on two separate projects. The first was studying fossil specimens in museums across the U.S. and Europe. The other project proved to be the next momentous event in Ungar’s life, both personally and professionally, an experience that impacted him deeply and reverberates today. He and his wife Diane went to Indonesia, to the island of Sumatra. They set up camp at Ketambe, a remote, mountainous area that at the time was the largest continuous tract of untouched lowland rainforest in Indonesia, and possibly all of Asia.

Combining Fleagle’s approach to using living animals to model behaviors of fossil species and Grine’s emphasis on teeth, Ungar observed and gathered information on the eating habits of four different species of primates - orangutans, gibbons, leaf monkeys and macaque monkeys – all living together in the rainforest. For one dramatic year, 10,000 miles from New York, he watched these primates, and though he had never taken a course in primatology and “had no idea how to study animals in the wild,” he collected information to test hypotheses about the relationship between tooth wear and behavior.

The experience in Ketambe was blissful and painful at the same time. His time with the primates inspired him and solidified his decision to make a career out of evolutionary biology, but early on, the monkeys did not cooperate.

“When I was in grad school, everything was simple,” Ungar says. “Animals with sharp teeth ate leaves, because they sheared and sliced them. Animals with blunt teeth ate fruits, because they pulped them. Animals with very thick enamel and very flat teeth crushed nuts, because that’s what their teeth told them they should be doing. That’s what they were designed to do, what nature selected for them. My first couple of weeks (in the field), everything was backwards. The fruit-eating monkeys were eating nothing but leaves, and the leaf-eating monkeys were eating nothing but fruits. I was ready to give up and go home. I’m like, obviously they hadn’t read the textbooks.”

Fleagle told him not to worry, to be patient, “‘the monkeys will teach you.’” And they did. Over time, Ungar began to see the monkeys and their dietary behavior differently. There were a few specific moments in the field that fundamentally changed the way he thought about the role of food and eating in evolution.

“I learned a very important lesson from these animals, and that is food choice is not driven by the shapes of your teeth or the size of your jaw, or even your gut. It's driven by what's available.”

THE BIOSPHERIC BUFFET CONCEPT

This revelation led Ungar to an idea, the “biospheric buffet concept,” which he describes as a giant smorgasbord or Chinese buffet where “nature sort of puts out different dishes” and animals chose what they want to eat based on what’s offered.

“Envision monkeys and antelopes bellying up to the sneeze guard with plates in hand,” Ungar says. “The choices they make define their place in nature… And, if you extrapolate from that, over time nature changes what’s available on the buffet. Animals have to adapt and change their choice or die.”

This idea, developed nearly 40 years ago, is still fresh in Ungar’s mind. It pervades his work today, and its application is one of his contributions to biological anthropology. As he puts it, it “moves the conversation in the discipline from what animals are designed to eat to what they really eat on a daily basis.” This, of course, depends on environment and how changes in the environment then drive evolution.

“This idea has driven almost everything I've done since,” he says. “It’s what underlies my interpretations of microwear.”

Observing primates and developing new ideas about how they and humans evolved weren’t the only things happening in the rainforest. Ungar and Diane showed up in the middle of a political insurgency, the Rebellion in Aceh. They checked in at the consulate and were grilled about where they were going and why.

On top of this, Ketambe was near the epicenter of a 6.8 magnitude earthquake that destroyed much of the two nearest towns. There were floods. At one point, Ungar and Diane were stuck on one side of the river for two weeks without food. They and others had to rely on fish that got trapped in the camp after the floods. Another town near them burned down. Through all of this, Ungar remained focused on his work.

Other parts of the Sumatra experience sound like Dinesen’s Out of Africa. Amid the natural disasters and unstable politics, Diane, a nurse practitioner, volunteered three days a week in the local clinics and then eventually opened her own clinic. She requested physicians in the U.S. send drug samples, which she dispensed to locals.

“I'm convinced that if she weren't such a good person,” Ungar says, “it could have been worse.”

DIGGING DEEPER TO UNDERSTAND DIET

When Ungar returned to the states, his post-doctoral advisor at Johns Hopkins Medical School, the celebrated paleoanthropologist Alan Walker, encouraged him to come up with a better way to do microwear analysis of teeth. At that point, Ungar and other researchers relied on “analog” techniques. On large cast models, they used protractors and compasses to measure and count scratches – sometimes hundreds on one tooth.

He studied the problem and, like so many other processes at the time, converted them digitally. Ungar worked with colleagues to develop a computerized, three-dimensional method for analyzing micro-textures on teeth. This method solved problems of conventional microwear analysis by reducing observer error and promoting efficiency and repeatability. Perhaps more important, for more than three decades now, Ungar’s microwear method has enabled him and other researchers to dig deeper, literally, to understand breadth of diet.

“I've written all these books and articles on teeth,” he says, “but I don't really care about teeth. Teeth are tools. It’s more about how we use teeth to understand the diversity of life on our planet, past and present. So, teeth in and of themselves are boring. What’s really interesting is what they can teach us. My passion is really in trying to understand the way the world works, or at least a little piece of it and how animals fit into it, how they came to be the way they are today.”

In May, Ungar learned that he was chosen to be a member of the National Academy of Sciences, one of the highest honors a scientist can achieve. He is the first and only University of Arkansas faculty member to be elected to the prestigious organization, founded more than 160 years ago by President Abraham Lincoln and scientist Alexander Dallas Bache. Ungar does not know who nominated him to be a member.

Not too shabby for 79th in his graduating class.

What’s the trouble with teeth? Ungar explains in this Short Talks From the Hill podcast.