THE SCIENCE BEHIND STRUCTURE

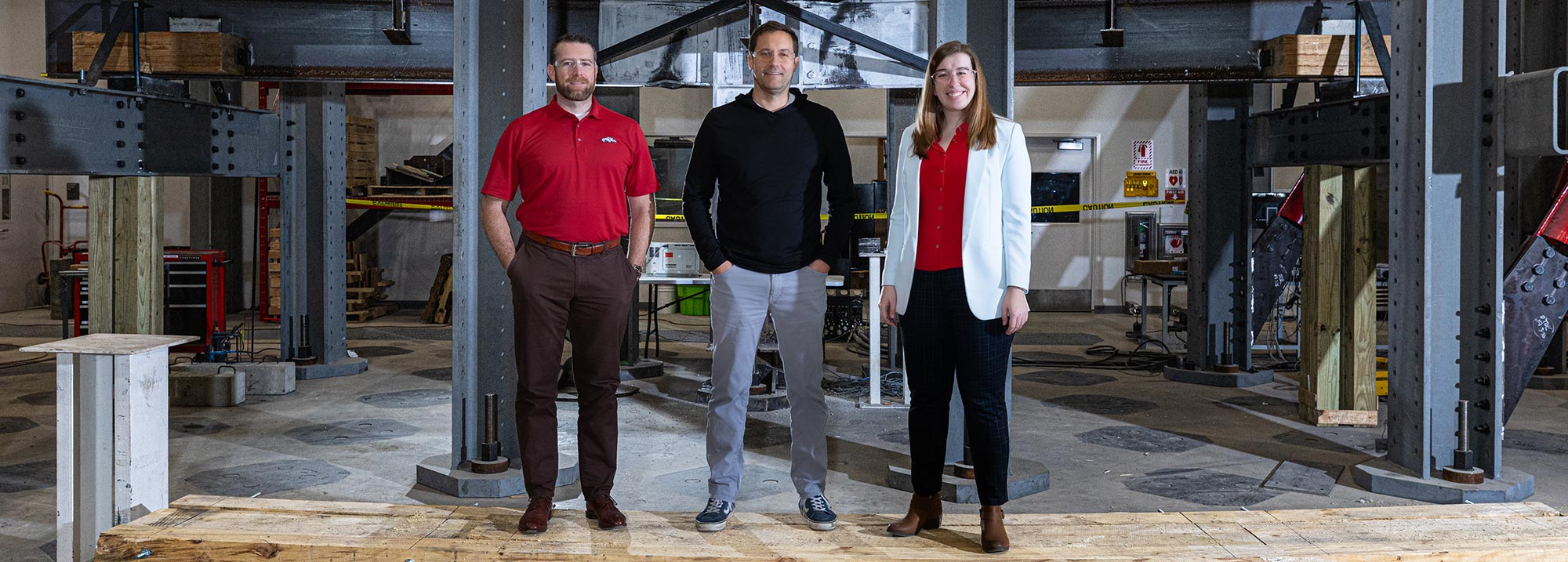

The buildings and bridges of the future will be safer thanks to the work of civil engineers like Cameron Murray, Gary Prinz and Morgan Broberg, three faculty members at the University of Arkansas.

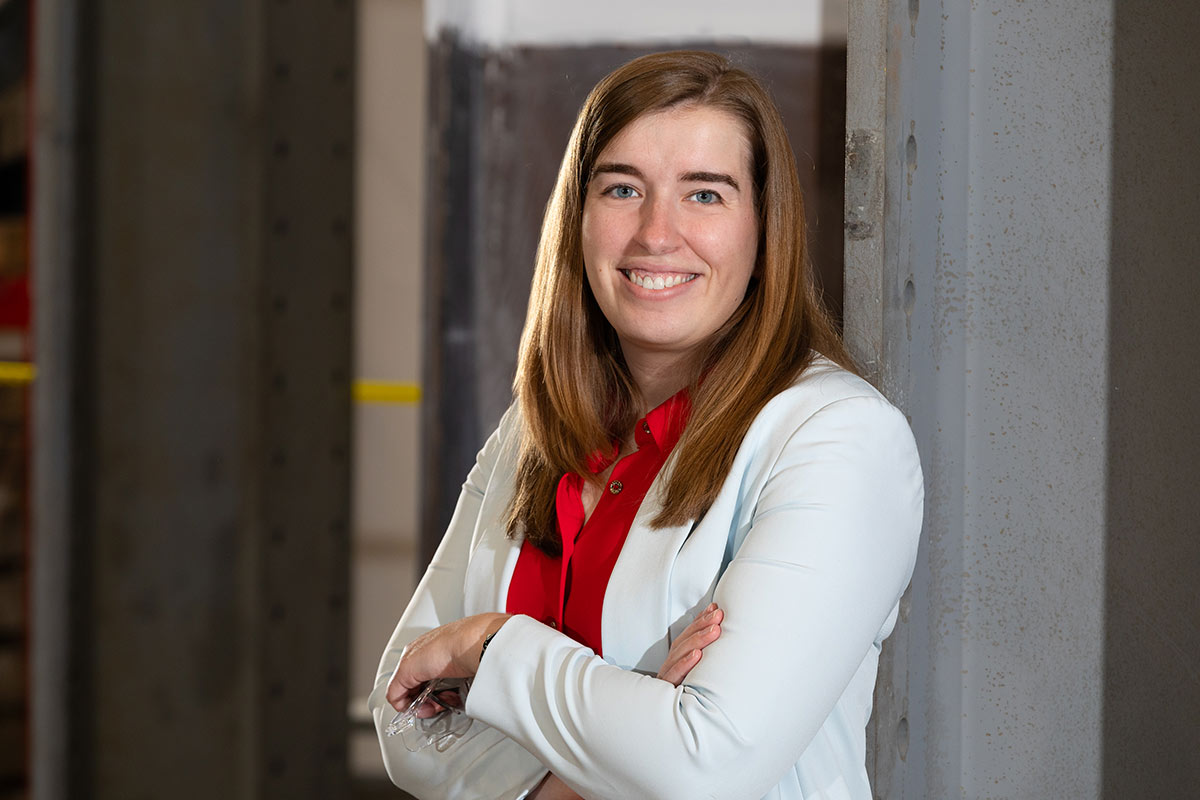

“You and I spend most of our time in structures, and if we’re not in a structure, we’re traveling on them,” says Broberg, an assistant professor in the College of Engineering. “Infrastructure is where we spend day in and day out, and, as researchers, we look at it as an opportunity to see how we can make it better. In civil engineering, no failure is acceptable.”

From developing a faster setting concrete to finding the breaking point of steel structures, Murray, Prinz and Broberg, along with their fellow researchers, are not only building more resilient buildings and more efficient bridges – they’re building a better tomorrow.

THE RIGHT MIX

When it comes to roads and bridges, associate professor Cameron Murray will have you know that there is a difference between asphalt, concrete and cement. Though the words are often used interchangeably by non-engineers, they’re actually very different things.

Murray explains that asphalt concrete is a mixture of rock and an asphalt binder. Asphalt is a sludgy, sticky, black tar-like substance that is a byproduct of refining petroleum products. It’s used as a binder to hold rocks together, because as it’s heated, it becomes more fluid and forms around the rocks. When it cools, you then have a solid. Concrete, and specifically the concrete Murray works with, is made from a different binder – a powder that is mixed with water to produce a chemical reaction that results in a rocklike building material. Cement, on the other hand? That’s the ingredient you mix with rock, sand, and water to make it harden and turn into a solid.

“It’s like yeast and bread,” he explains. “You need yeast to make bread, but yeast and bread are not the same thing. Yeast is just one of the ingredients.” Continuing with the yeast-bread analogy, one might say that Murray works with a rapidly rising yeast; his primary research interest is fast setting concrete materials that can be used for repairs or speedy construction methods. While regular concrete must be left to cure for a month before sustaining traffic, Murray’s mixture can reach its needed strength in a matter of hours.

“If there’s a bridge or something that has damage to it, our special concrete formulations can be poured in to replace the sections that are damaged, and the bridge can be up and running in a matter of hours.”

These concepts can also be applied to precast concrete, which are components that are assembled in a factory and then shipped to a job site for assembly – like for parking garages.

In 2023, faculty in the College of Engineering – including Murray and associate professors

Michelle Barry and Wenchao Zhou – received a grant of nearly $3.5 million to advance

3D concrete printing.

In 2023, faculty in the College of Engineering – including Murray and associate professors

Michelle Barry and Wenchao Zhou – received a grant of nearly $3.5 million to advance

3D concrete printing.

Unsurprisingly, Murray works closely with ARDOT, the Arkansas Department of Transportation, as well as with local contractors and industry groups. As a native Arkansan, he views this collaboration as just another example of what the university’s research can provide to the state as a land grant school.

“If the University of Arkansas wasn’t here, I don’t know who would be helping with these types of projects,” he says. “A lot of home-grown talent actually stay in the state and contribute to the industry. Even people who come to school here from out of state end up liking it a lot and decide to stay in the area.”

Having grown up in Maumelle, Arkansas, Murray is one of the former. And since he’s joined the university as a faculty member, he’s been involved in numerous research projects that have brought in millions of dollars of funding, including a $500,000 grant from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to design rapidly constructable bridges.

“I’m very fortunate that I get to do something that’s very practical but that also has a really high impact on the world, including teaching students and passing on my knowledge to other people,” he says.

Listen to Cameron Murray explain his work with concrete on Short Talks From the Hill.

THE MAN OF STEEL

While concrete is very strong in compression, it’s not ideal under tension. That’s where steel comes in – it serves as a reinforcement in areas where the concrete would experience this tension.

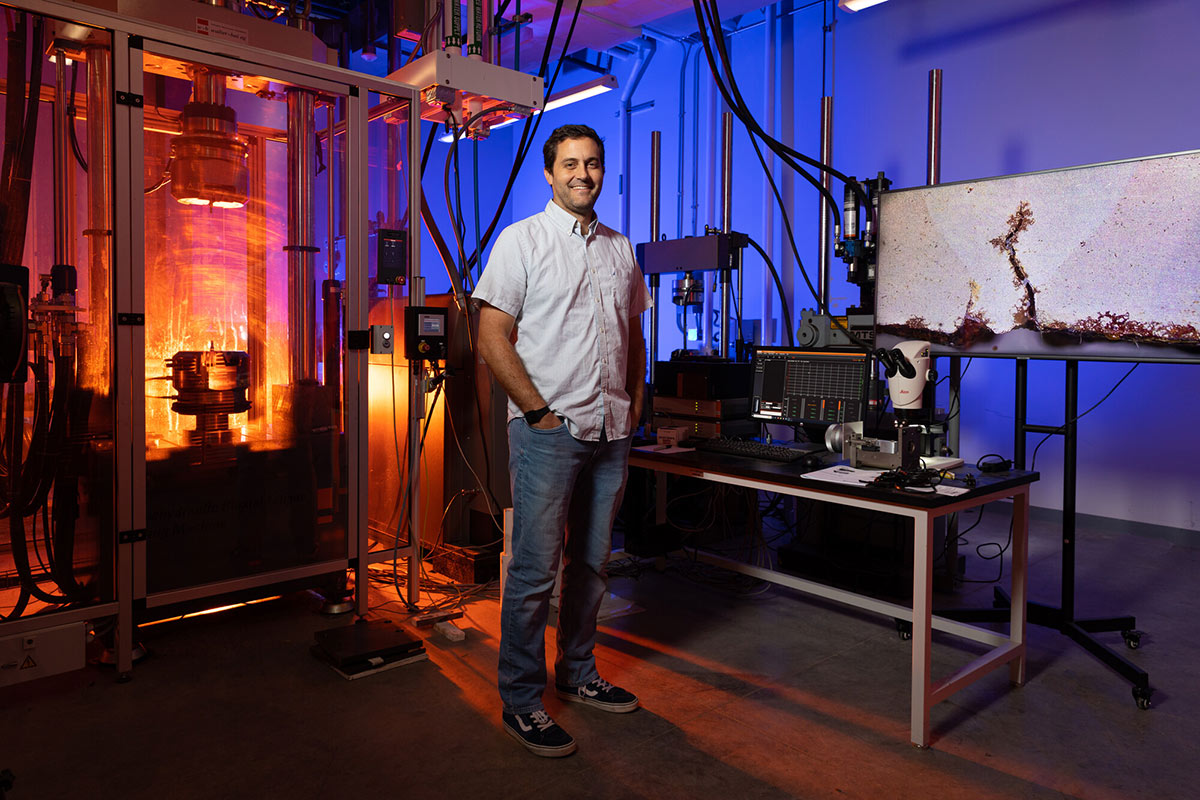

Professor Gary Prinz works extensively with steel – particularly steel infrastructure, like bridges and buildings – and often collaborates with Murray and Broberg on research projects.

“I’m looking at structures that are subjected to loads that are repeated or extreme, like traffic or earthquakes,” he says. “My research mainly focuses on a very specific type of fatigue and fracture in our metal structures.”

A good analogy, he explains, is like bending a paper clip. “Imagine fiddling with a paper clip at your desk, bending the metal material back and forth. After a while, the paper clip separates into two pieces.”

“It gets tired and will break, and our large infrastructure is no different,” he says. “Take traffic, for example – traffic is just a lot of tiny loads applied over and over, and under the wrong conditions the steel materials can get tired over time. When this happens, you may start to see cracks. We work on understanding when and why the materials get tired, so design engineers can ensure the steel will ‘stay awake’”

Prinz’s work takes the same physics applied to bending the paper clip to a larger scale – like earthquakes bending and moving steel beams in buildings. And he has another clever analogy for explaining how they tackle that problem.

“In the seismic design of a steel building, the general approach to keeping people safe is similar to the way an electrician might keep your house safe from an electrical fire,” he explains.

Most people can relate to the experience of having an overloaded circuit in their home and the resulting trip of a breaker switch. If the breaker doesn’t trip, the wires could be overloaded and result in a fire.

“So, what we do in our design of steel buildings for earthquakes is put structural ‘circuit breakers’ in very specific locations,” he says. “We basically design fuses into the building to accumulate damage and dissipate the seismic energy in a safe and controlled way, to make sure the structure doesn’t collapse.”

The trick is making sure that these elements – whether a brace or a connection or a specific welded region – can absorb that energy without breaking, so the building performs its function of keeping people safe during earthquakes. That’s where Prinz’s work comes in – he and his fellow researchers subject their structural fuses to extreme tests in the lab to ensure that – just as with a circuit breaker – they’re “tripping” when they should.

THE BEST OF BOTH

Working alongside Prinz is Broberg, who primarily works on steel and concrete composites – the big building blocks that are used to make structures, bridges or most any kind of infrastructure. Most of her work is done with steel composites and examines how she can take steel and combine it with concrete to get the best of both materials. Broberg’s work has contributed to the use of these composites in high-rise buildings like Rainier Square in Seattle and 200 Park Ave. in San Jose.

“Concrete is really efficient in compression, like supporting your weight when you stand on it, but it does not resist tension. Steel can resist those tension loads. Used together you can create very efficient structures,” she says. “We want more efficient, sustainable, and resilient structures, so when infrastructure is stressed, we can get back to normal more quickly.”

Broberg explains that roads and bridges are currently built out of many construction materials, including steel, concrete and wood. Nowadays, structures are required to handle bigger loads than ever before, due to larger and more frequent natural events (like forest fires, hurricanes and earthquakes), more cars on the roads (including autonomous vehicles) and explosive blasts.

“Our attitude towards risk changes over time. What used to be an acceptable level of risk might not be anymore,” she explains. “So, we research how to build the structures stronger in the first place so they can withstand larger natural hazards, higher loads and even man-made hazards, like blast or impact.”

THE SCIENCE OF DESTRUCTION

Broberg, Murray and Prinz all agree that their work would not be possible – or at least much harder – without CEREC (“See-Rec”), the nickname for the Grady E. Harvell Civil Engineering Research and Education Center. Opened in 2021, CEREC has been called a “game-changer” for allowing researchers a greater opportunity to test their work in a controlled setting, allowing them to better understand how their research will perform in nature. Prior to its opening, the state of Arkansas did not have an in-state capacity for full-scale structural testing.

In work like Prinz’s, who is director of the center, it’s not always possible – and definitely not preferable – to wait for a natural disaster to occur before examining how structures perform.

“Learning from nature is an expensive game to play,” he says. “It’s much less expensive to have these facilities, like CEREC, where we can do very controlled experiments and gain understanding in a very controlled way that’s safe and doesn’t put society at risk.”

In late 2024, the National Institute of Standards and Technology awarded $5 million to researchers at the U of A, including Prinz and Murray, to develop a center for large-scale testing of seismic systems. The award allows for the purchase of hydraulic loading equipment, materials testing equipment, state-of-the-art data acquisition devices and key upgrades to the existing CEREC testing facility.

Since its opening, researchers affiliated with CEREC have garnered more than $21.5

million in research awards.

Since its opening, researchers affiliated with CEREC have garnered more than $21.5

million in research awards.

The facility is also an exceptional laboratory for the students who work with its researchers.

Prinz remarks, “The students who work at CEREC are getting a one-of-a-kind experience in their education because not only do they get to take classes, but then they get to go into the lab, weld up assemblies, bolt things together and rip them apart. They get to calculate how much force it might take to break or damage one of these components, and they get to feel what it’s like when it does break. It’s a unique experience for sure.”

As a new faculty member, Broberg says she was drawn to the U of A because of CEREC.

“I had opportunities elsewhere, but I chose to come here for the combination of the great facilities as well as the world class researchers,” she says. “In my work, I do a combination of large-scale testing and computational modeling. As part of that, you need facilities to do the large-scale testing. It’s a line in the sand, because there’s no point to me being somewhere that doesn’t have facilities that can support what I do. And there’s only a handful of facilities across the U.S. that have the capabilities that we have here.”

Murray agrees. “We’ve gone from having nothing like this facility to having one of the best ones in the country.”

Watch Prinz and U of A students utilize CEREC’s capabilities in the Discover RED video, “Stressing Steel.”