MAKING WATER SAFER

Professor Julian Fairey is engineering safer drinking water.

What’s in your water? Julian Fairey can likely tell you.

Inorganic chloramines are commonly used to disinfect drinking water to safeguard public health from diseases like cholera and typhoid fever.

Fairey, an associate professor in the College of Engineering at the University of Arkansas, researches the chemistry of drinking water disinfectants and environmental sampling. He’s working to develop new technologies to reduce the risks posed by pollutants in sediments and drinking water and recently led the discovery of a new compound in chloraminated drinking water – something that’s consumed by more than 113 million people in the United States alone.

“Chlorination, with what we refer to as free chlorine, is the most common drinking water disinfectant used in the United States and worldwide,” Fairey says. “What we’re referring to here is chloramination, which stems from chloramines, which are formed from reactions between chlorine and ammonia. This is the second most common disinfectant used here in the United States in our drinking water distribution systems.”

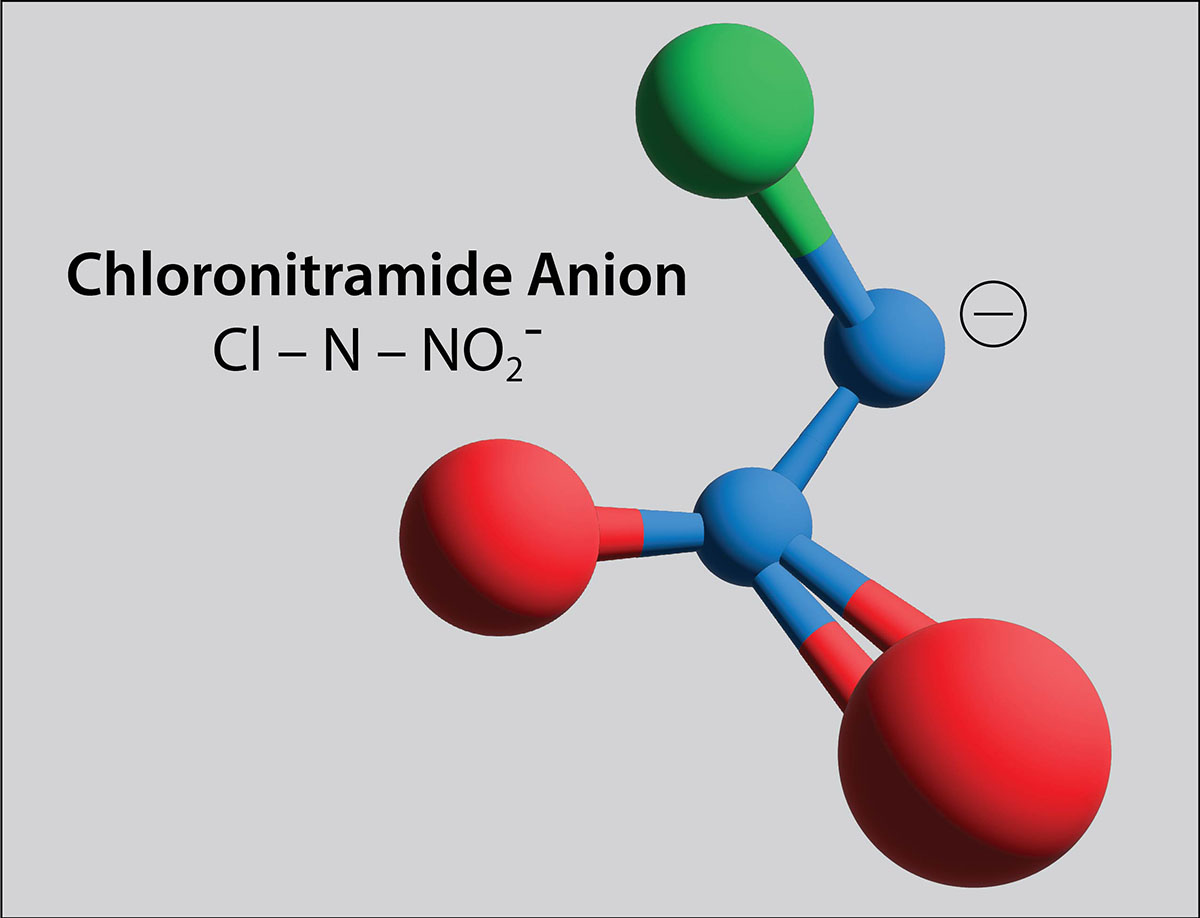

Fairey, along with a team of researchers from the United States and Switzerland, have now identified chloronitramide anion, chemically expressed as Cl−N−NO2−, as a compound that forms in chloraminated drinking water. So, when chloramine disinfectants are added – and decompose, as they do naturally – chloronitramide anion forms.

THE SWISS SAMPLE COMPARISON

Fairey synthesized the compound in his lab – something that had never been done before – and samples were then sent for analysis to his colleague, Juliana Laszakovits, a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of Kristopher McNeill, Professor of Environmental Chemistry at ETH Zurich.

“Chloraminated drinking water is common in North America, but chloramination is not really practiced in Switzerland,” Laszakovits explained, “and there’s no chloronitramide anion in Swiss waters.”

McNeill noted that this “actually allowed us to use Swiss tap water as a control in the study.” He added that the current study focused on water systems in the US. However, Italy, France, Canada, and other countries also use chloramination and could be potentially affected as well.

RESEARCH ON TAP

While the toxicity of chloronitramide anion is not presently known, its prevalence and similarity to other toxic compounds is concerning and warrants further study to assess its public health risk. Simply identifying the compound has been a challenge and a breakthrough.

“We first realized this compound formed in drinking water in the early 1980s,” Fairey says. “There was a Ph.D. student at Cal Berkeley who recognized that when chloramine disinfectants decomposed in pure water, they formed this unknown compound. We knew it formed because he was measuring the ultraviolet spectra of the water, and as chloramines decompose, this absorbance spectra increased.”

Fairey himself began trying to unravel the mystery of the unknown compound 10 years ago.

“It’s a very stable chemical with a low molecular weight,” Fairey says. “It’s a very difficult chemical to find. The hardest part was identifying it and proving it was the structure we were saying it was.”

Fairey was the first co-author on a paper published in Science* that identified chloronitramide anion.

Fairey was the first co-author on a paper published in Science* that identified chloronitramide anion.

Fairey explained in a previous interview, “It’s well recognized that when we disinfect drinking water, there is some toxicity that’s created. Chronic toxicity, really. A certain number of people may get cancer from drinking water over several decades. But we haven’t identified what chemicals are driving that toxicity. A major goal of our work is to identify these chemicals and the reaction pathways through which they form.”

Identifying this compound is an important step in that process. Whether chloronitramide anion will be linked to any cancers or has other adverse health risks will be assessed in future work by academics and regulatory agencies, such as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. At the very least, toxicity studies can now be completed on this compound thanks to this discovery.

Fairey explains how drinking water is treated on the National Science Foundation News podcast, NSF’s Discovery Files.

“Even if it is not toxic,” Fairey explained, “finding it can help us understand the pathways for how other compounds are formed, including toxins. If we know how something is formed, we can potentially control it.”

Fairey’s focus now is producing chloronitramide anion at relatively high concentrations and isolating it, so he can share it with others who study its toxicity.

ENGINEERING SAFER WATER

In addition to this discovery, Fairey also developed a sensor system to detect the early onset of nitrification events in water systems.

He explains, “One of the drawbacks of chloramine systems is that basically when chloramines decompose, not only do they form this chloronitramide anion but they form ammonia, and ammonia is food for microorganisms. Nitrification is the oxidation of ammonia to nitrite and nitrate.”

When microorganisms start to grow, they release materials into the water that fluoresce. So, Fairey and his team developed a real-time fluorescence-based sensor system to detect the early onset of nitrification events. This system provides an early warning of nitrification that could benefit water utilities that experience nitrification events by alerting them to the problem sooner and permitting less costly remedial actions.

As Fairey explains it, the current system for detecting nitrifying bacteria in the water system is “very manual. People have to go out and take samples at various points in the system and bring it back to the lab to test. In a place like Houston, the system is a thousand miles long.”

What his sensors would do is collect data continuously in real time and send the data back without the need for manual collection of water samples, identifying a problem before the water degrades. Theoretically, disinfectant boosting stations around the city would then automatically trigger needed responses.

“We can adapt responses sooner, improve our detection and make the system safer,” he concludes.

It’s an advancement that makes you want to raise your glass with appreciation. Thanks to this innovation, Fairey is potentially changing how water treatment and detection is done in the U.S. and beyond – making those eight glasses you consume each day safer to drink.

Listen to Fairey explain his discovery and research on the Short Talks From the Hill podcast.

Read more about Julian Fairey in this Technology Ventures’ Inventor Spotlight and discover how the University of Arkansas is building a better world at arkansasresearch.uark.edu.

*Joining Fairey and Laszakovits as co-authors on the paper are Huong Pham, Thien Do, Samuel Hodges, Kristopher McNeill and David Wahman. Pham, Do and Hodges are all former Ph.D. students at the University of Arkansas who contributed to this research in Fairey’s lab. In 2022, McNeill hosted Fairey at ETH Zurich as a visiting professor as part of his sabbatical where they worked with Laszakovits on this study. Wahman is a longtime collaborator with Fairey’s lab group and is a research environmental engineer at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.