Dedication in Waves

Breast cancer is the second most common cancer for women in the U.S., and many women find themselves facing recurrence of the disease over time. Magda El-Shenawee is working to reduce this threat through new imaging technologies that help surgeons make more precise decisions about cancerous tissue during lumpectomies.

“When the surgeon takes the tumor out, what remains?” El-Shenawee queried. “It’s hard to determine where the cancer ends and healthy tissue begins. If the surgeon doesn’t remove enough, the cancer comes back. And if too much healthy tissue is removed, the patient risks having a mastectomy. Preventing it from metastasizing is the key, and the margins we examine help ensure the correct amount is being removed.”

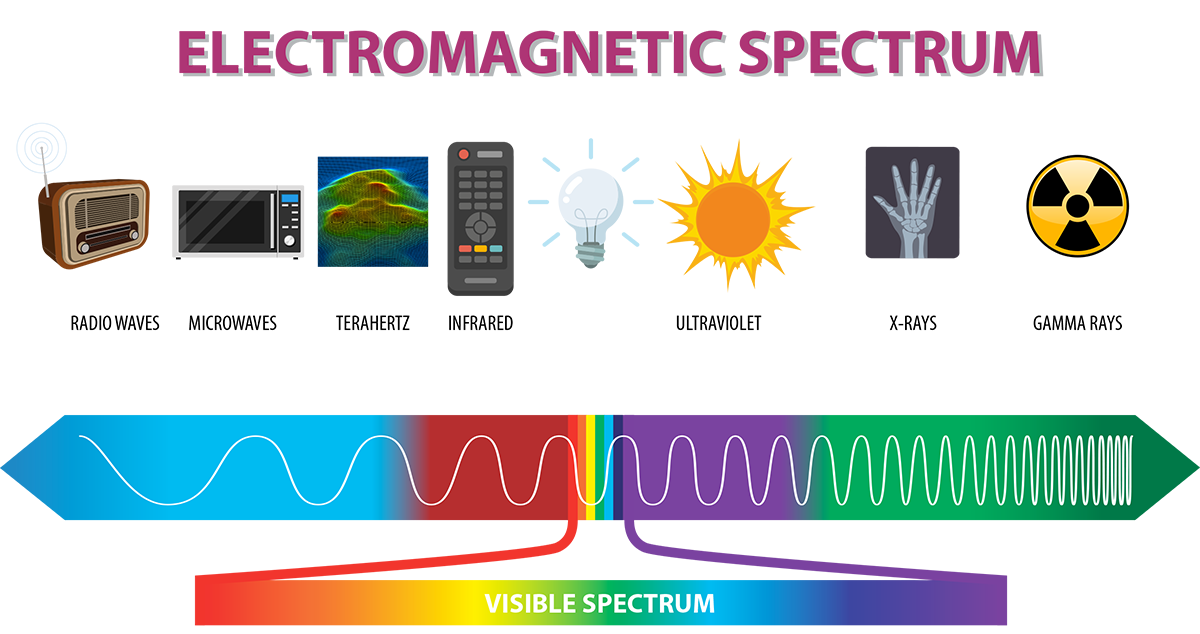

Using a new imaging technique involving terahertz frequencies – a frequency range found between microwaves and infrared waves – El-Shenawee and her team can help surgeons more accurately determine the appropriate amount of cancerous tissue to remove by making it easier for them to clearly see tumor margins during lumpectomies.

Her technique can help ensure that no cancer remains, thereby reducing the possibility

of the cancer developing further or the patient returning for a second surgery.

Her technique can help ensure that no cancer remains, thereby reducing the possibility

of the cancer developing further or the patient returning for a second surgery.

El-Shenawee notes that the percentage of second surgeries is nearly 25%, adding stress to an already highly charged emotional experience. Imagine, she says, being a woman who has just undergone your initial surgery only to find out that the cancer has returned and another operation must be scheduled.

It’s a problem she’s not tackling alone; in fact, there’s an entire army of researchers across the country and the world who are trying to combat the disease. And El-Shenawee realizes that what she contributes to the research is an important part of the solution.

“It’s amazing the amount of work being done nationwide,” she says. “And yet, one out of eight women still gets breast cancer.”

Embracing Challenges and Tackling Life's Landmines

El-Shenawee’s story began in Egypt, where she grew up knowing that she always wanted to be an engineer. Her father, who was a mechanical engineer, tried to dissuade her from this path and encouraged her to consider medical school instead. “Engineering is hard for women,” he warned. “You will suffer.” El-Shanawee knew he wanted to protect her from the treatment she might receive as a woman in a predominantly male field, but she was undeterred. “It’s a very challenging position for women,” she said. “But I like a challenge, and I like being able to accomplish something and make a difference.”

"I like a challenge, and I like being able to accomplish something and make a difference."

She found her research focus as a post-doc at Northeastern University, where she worked on a project detecting landmines made of plastic, which – unknowingly – would launch a career focused on using imaging techniques to solve complicated real-world issues.

Enter terahertz radiation, which is unique in that it is non-ionizing – unlike x-rays, which can expose patients to additional cancer risks from exposure over time. El-Shenawee uses this technology to differentiate healthy breast tissue from cancerous tissue to help save lives.

El-Shenawee encourages more diversity and inclusion in the field of electrical engineering,

especially for women. She hopes to accomplish this goal through her involvement with

the Institute for Electrical and Electronics Engineers, where she was elected to serve a three-year term on the administration committee, known as AdCom, in February 2021.

El-Shenawee encourages more diversity and inclusion in the field of electrical engineering,

especially for women. She hopes to accomplish this goal through her involvement with

the Institute for Electrical and Electronics Engineers, where she was elected to serve a three-year term on the administration committee, known as AdCom, in February 2021.

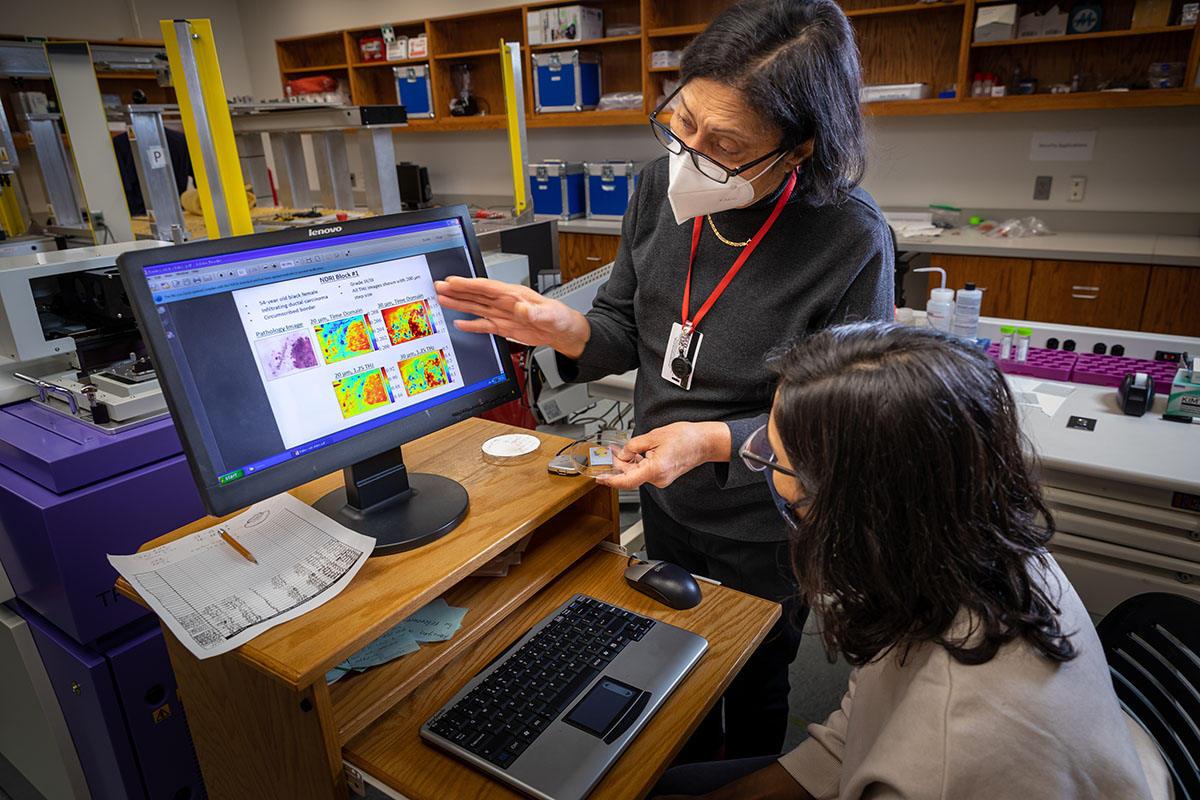

Tissue, Tumors and Terahertz Technology

El-Shenawee’s new research centers on diversifying the way signals are sent and received through cancerous tumors – called wave polarization – and the different results they yield. She and her team produce many different images using the terahertz technology and layer them to get a better, fuller picture of the composition of the tumor in question. Their biggest breakthroughs come from imaging freshly excised tumors and comparing those results to the findings from a pathologist, who helps interpret the images. All this simulates what could eventually be done in an operating room, given the appropriate equipment, training and time, to help ensure all cancerous tissue is being removed and the maximum amount of healthy tissue remains.

El-Shenawee’s research on breast cancer tumors and the use of terahertz antennas

is applicable to other areas. In a paper published in 2017, El-Shenawee proposed an

idea for improving the efficiency of terahertz antennas, which could potentially be

used for high-speed electronics wireless communication.

El-Shenawee’s research on breast cancer tumors and the use of terahertz antennas

is applicable to other areas. In a paper published in 2017, El-Shenawee proposed an

idea for improving the efficiency of terahertz antennas, which could potentially be

used for high-speed electronics wireless communication.

In 2018, she said, “If we can advance terahertz antennas by advancing their output power, the U.S. will be using a band of frequency that no other country has the technology for yet.”

Currently, more than 50% of the freshly excised tumor tissue examined can be differentiated, but El-Shenawee wants that total to increase to at least 90%.

“It’s exciting to get meaningful results,” she says. “We’re not doing this research to satisfy ourselves. We want to publish it and help other researchers.”

From Intrigue to Inspiration to Implementation

El-Shenawee was introduced to terahertz technology at a workshop and was immediately intrigued, though she had no equipment available for her research. Various grants have allowed her to purchase equipment and set up her own lab, working with her U of A students and collaborating with fellow faculty members along the way. The students who work in El-Shenawee’s lab are right by her side, gaining first-hand knowledge about problem solving and critical-thinking skills.

“The good students are everything,” she says. “I have the ideas, but they implement them. It takes some time to train them and they have to be self-motivated, but they have all found very good jobs in national labs, U.S. companies, or with other universities after they have moved on. They inspire me, and if they don’t, I inspire them.”

A Selection of Grants Garnered by El-Shenawee:

A Selection of Grants Garnered by El-Shenawee:

$424,545 from the National Institutes of Health, announced in Oct. 2021

$16,502 from the University of Arkansas Women’s Giving Circle in Jan. 2021.

$456,070 from the National Science Foundation for El-Shenawee to research high-frequency antennas in April 2020.

$424,081 from the National Cancer Institute, part of the National Institutes of Health, in March 2017.

$388,913 from the National Science Foundation in May 2014.

The terahertz technology used by El-Shenawee and her team is housed in a couple pieces of equipment: one that is designed to scan tumors and smaller cancer samples and another used for bigger applications. Grants provided the funding for her research instrumentation, and she continues to finesse its capabilities by determining what it is picking up on the scans and what it is not. It’s a continual process of trying, tweaking, and trying again.

“I tell students all the time that we don’t make jumps in research – we take small steps,” she says.