THE COURTESY TO LISTEN

When Elliott West arrived at the University of Colorado in 1967 to begin his master’s degree in history, he was shocked to find out he had to specialize in a particular area. He studied journalism as an undergraduate and wasn’t familiar with the demands of history. He’d enrolled at U.C. on the strength of his attraction to the state, where his grandmother lived and his family vacationed every summer to escape the Dallas heat where he was growing up. As his family had deep southern roots, he suggested southern history might make a good focus.

“We don’t have anybody here who does southern history,” he was told.

“What do you do?” West asked.

“We do a lot in the west.”

“Okay, I’ll do the west,” he said cheerfully. “So they sent me down to see Robert Athearn, who was a prominent western historian. I took classes and a seminar from him and that’s all she wrote. I was suddenly in love with it. And loved it ever since.”

While it may have started as an arranged marriage, it was nevertheless an enduring one. Still, it’s strange to think such a celebrated career began with so little intentionality. It makes you wonder what might have happened if his grandma lived in Hawaii.

Surely a masterwork on the history of big wave surfing?

An academic career that began with that arbitrary decision more than 50 years ago prospered into a 43-year tenure with the University of Arkansas as a Distinguished Professor of history and eventually concluded with West’s retirement in 2022 at the age of 77. At that point, he’d published eight scholarly books, 90 articles and garnered enough prizes and recognitions to fill a pie safe. For West, the highpoint was an invitation to be the Harmsworth Visiting Professor of American History at Oxford University for 2017-18. Established in 1922, the program hosts an American historian every year and is considered among the highest honors in the field. You cannot apply. You must be invited.

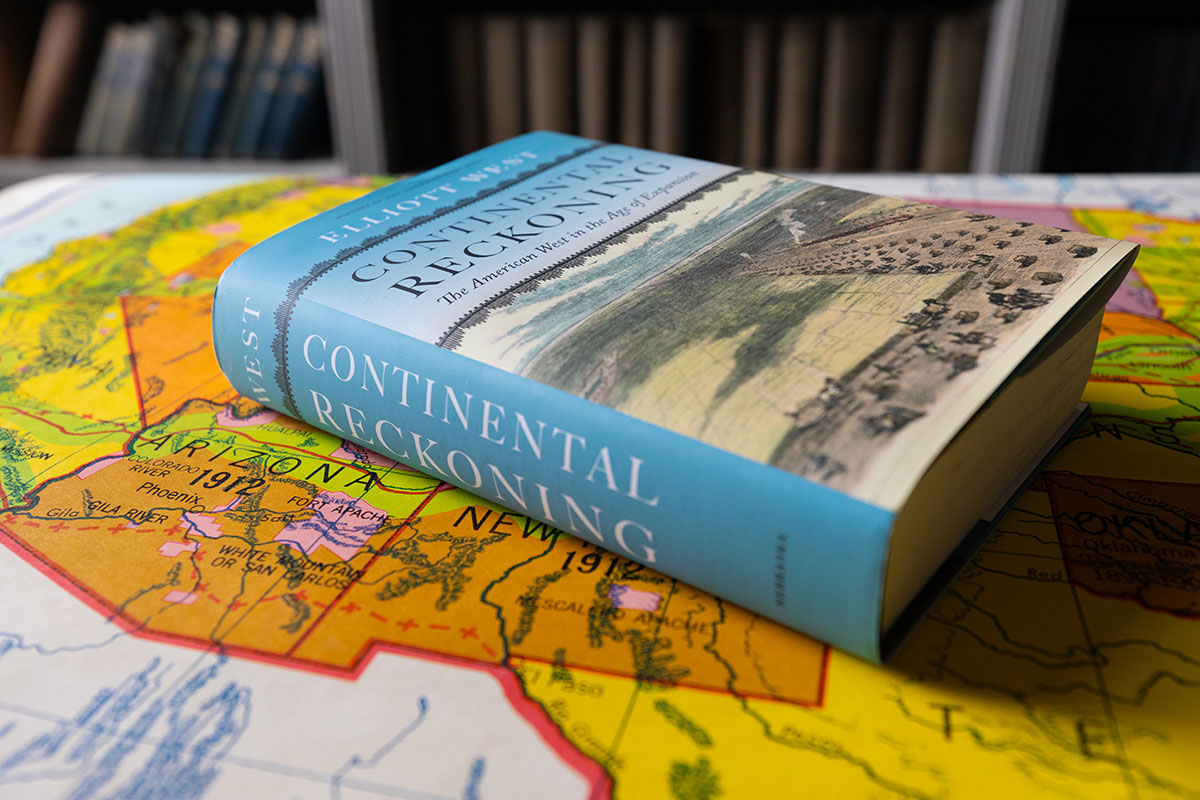

For most people, that would be a wrap on an enviable career. But West saved the best for last. In 2023, he published his masterwork, Continental Reckoning: The American West in the Age of Expansion, a monumental examination of the American west from the 1840s to the end of the 19th century. The book was effectively the synthesis and fresh interpretation of the preceding 50 years of historical scholarship West had spread across all those earlier books and articles.

Reckoning has since won the 2024 Bancroft Award, which recognizes historical works of “scope, significance, depth of research and richness of interpretation” and been a finalist for the 2024 Pulitzer Prize for History. On their website, the Pulitzer committee described the book as a “masterly crafted and comprehensive narrative of how our nation’s history unfolded across the American West and how the West, no less than the Civil War, profoundly shaped the rise of modern America.”

West has also appeared in the Ken Burns documentary series, The American Buffalo, as well as been a guest on the most popular podcast in the world, The Joe Rogan Experience. The two- hour conversation has been parceled into shorter clips posted on YouTube that have received millions of views and almost uniformly glowing comments.

“Good thing I’m retired,” West quips. “I wouldn’t have time for all this stuff.”

Rogan, he explains, invited him onto his podcast (episode No. 2058) because he’d heard West on another podcast, Meateater, which has an outdoors bent. Prior to participating in the Meateater podcast, West admits not only had he not heard of the podcast, he didn’t know what a podcast was (but the host was willing to fly him to Montana to talk about American history, so it seemed like a fun opportunity). West further admits he had never heard of Joe Rogan prior to Rogan reaching out to him. But his son set him straight on both accounts.

If West isn’t keeping up on current developments, it’s somehow fitting for a man who has spent most of his life digging through historical archives and projecting the lives resurrected there onto the former trails and battlefields and grasslands they once walked. Even his surname is oddly appropriate for a historian who has had his gaze fixed on the American west since 1967.

HISTORY AS A MORAL ACT

Contrary to the opinion that “history is just one damned thing after another,” (apocryphally attributed to Henry Ford), West believes that history is essential to being a human being.

“History is essentially collective memory,” he explains. “As far as we know, we are the only organism on earth that has a memory beyond its own lifetime. That sets us apart. History also involves imagining your way into the lives of other people. And to me, that is another essential human act, specifically another essential human moral act. You know, morality is based on compassion and being able to imagine and picture yourself as other people. So when you're doing history, whether you're writing, researching, or reading it, you are also exercising a kind of moral muscle.”

For West that essential moral act is best practiced in the fields trod by our forebears and in the archives where their lives are waiting to be reclaimed.

“I love musty archives,” he says. “I love archival research. You go there to get a sense of what it was like at the time. … I think the archives are a place where tens of thousands of people are trying to tell you their stories. We ought to have the courtesy to listen to them.”

To make his point, he cites a diary he found in Montana written by a man traveling up the Bozeman Trail to Virginia City: “This guy was going along and he wrote very succinctly,” explains West. “You know, ‘We stopped here.’ ‘Good grass.’ Saw a lot of buffalo.’ ‘Looks like signs of Indians.’

“And all of a sudden it stopped. One day he wrote, next day nothing. So I went to look at the guide for the archives and found out he was killed by Indians. So I’m holding in my hand this document, this diary, that had been held in the hand of a man who died violently the next day on the Bozeman. Something about holding that diary — you know, touching this paper that this guy touched, it puts you right back in that story.”

“You’ve got to do the archival research,” he insists, “you’ve got to put your nose in it. You’ve got to work like hell to try to reconstruct as much as you can what people did and the environment they did it in. And then you’ve got to go there to get a sense of what happened at the time.”

He further describes visiting the Bear Paw Battlefield on a cold morning on July 4, where the Nez Perce surrendered forty miles from the Canadian border. West was working on The Last Indian War: The Nez Perce Story, retracing the path the Nez Perce followed during their 1,100 mile trek to evade the U.S. Army. He was car camping, so cold he had trouble making his camera work, and the irony of the date was not lost on him. On Independence Day, he was at the location where the Nez Perce lost theirs, forced onto a reservation after their defeat.

This underscores a larger irony. He describes this period of time as a ‘great moral highpoint’ for the country, with the emancipation of people who had been enslaved for generations. But while four million people were gaining their freedom, thousands more were losing theirs. After going where they liked for 16,000 years, the Native Americans became like prisoners on their own land. Like enslaved persons earlier on plantations, they were only allowed to leave their reservations with a pass.

For West, this is the riddle of the West, the way in which great triumph and great tragedy ran on parallel tracks at a time of national transition: emancipation balanced against the defeat and dispossession of Indian peoples and the imposition of the reservation system, the conclusion of the transcontinental railroad balanced against the massacre of Lakota at Wounded Knee. Perhaps this is why he also felt compelled to return to it time and time again, drawn to these tensions and contradictions.

“There are humble people who have a lot to be humble about, and then there is Elliott West. His accomplishments are too numerous to list here so I will just say Elliott is the Charles Portis of American history — unassuming, a master of detail, erudite, uncannily discerning, and, above all, funny. He forces anybody around him with any self-respect to become a better scholar, a better writer and a better person.”

- Richard White, Margaret Byrne Professor of American History, Emeritus, at Stanford University and two-time Pulitzer finalist in history

THE CHARLES PORTIS OF AMERICAN HISTORY

The compassion and sensitivity that characterize West’s books are not limited to them. Colleagues and former students speak effusively of him.

Justin Gage, an assistant professor of history of the American west at the U of A, was a former student of West’s who returned to the university as faculty after West retired.

“When I became a teacher,” Gage says, “I wanted to emulate the teachers that I liked the best. You want to be the teacher you enjoyed, and Elliott's teaching ability is unmatched. I mean, he’s, genuinely enthusiastic about teaching people new things. Probably because he loves to learn new things himself.”

Gage adds that West impacted him as a faculty member, too. “He such a personable guy. He’s such a likable guy. I think he's very much concerned about other people. His advice was basically ‘be a good colleague. Be someone that’s easy to deal with. Be someone that is decent to other people.’ That’s probably the best professional advice you can give.”

This impression is reinforced by U of A chancellor Charles Robinson, who arrived as a young history professor in 1999. “Elliott was the historian I wanted to be,” Robinson explains. “When I came here, I mean, he was like a star historian. And I thought, ‘man, if I could ever become like Elliott West in any way, that would be real success.’

“I never did, but he still gave me a sense of what was possible. And again, the fact that he was so accessible, so down to earth. … You wouldn't have ever thought that he would have such humility. It was a genuine humility. He gave me time and attention and helped me to be able to get tenure and ultimately become a full professor.”

University of Arkansas chancellor Charles Robinson discusses the impact of Elliott West on his career.

THE FINAL RECKONING?

Perhaps the final and most important question is whether Reckoning will be the capstone to his career or if he’s got another book in him.

“I’m not sure I’ve got the energy or the time for another one,” West admits. “Books take a long time and they’re hard, hard work. Wonderful and fun work, but hard.”

So maybe he’ll continue on the podcast circuit as long as they keep inviting him. But if he were to write another book? Well, it just might be about how so many scientific breakthroughs took place out West, particularly during the era that Reckoning examines. This included huge advances in the fields of paleontology, biology, geology and medicine. For now, West makes no promises of another book, but he intends to keep reading up on how these fields first developed.

But maybe, just maybe, like a retired lawman reaching for his Winchester above the fireplace one last time because no one else will bring the stagecoach robbers to justice, West will reach for his typewriter one last time, think hard about the past and the people who populated it, and craft another classic.

And by the way? Shhhh. Let’s not tell Elliott about YouTube just yet.